Why Giving Up on a Global Climate Change Treaty Is A Good Idea

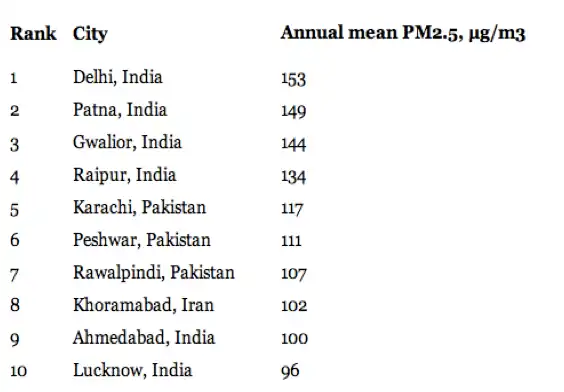

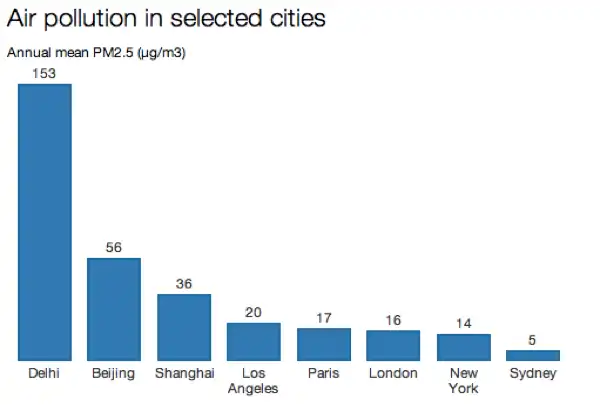

The air hung with a heavy grey fog and the city seemed to be laboring sluggishly beneath its weight. We watched the numbers slowly climb - 350 µg/m3…415 µg/m3…460 µg/m3…we held our labored breathes and waited. Would it make it? Was it possible? Then, finally! 550 µg/m3 followed by an ominous message “beyond index”. There was a nervous laugh, "haha guys we broke the scale!” If you’re a sophomore here at NYU Shanghai then you doubtlessly remember that day. Classes were cancelled, facemasks were handed out en masse and the day was spent screen shotting the American Embassy’s Air quality index and posting on Facebook or WeChat. However, as bad as that day was to experience, it’s much worse when we put it in context. Shanghai is actually considered to be one of the top fifteen cleaner cities in China, with a mean AQI ranking of 36 µg/m3 . Beijing meanwhile, infamous worldwide for its pollution problem, is definitely in the top five most polluted cities in China with an average of 56 µg/m3, but falls far short of number one, the dubious honor of which goes to Lanzhou. But that’s not even the worst part because Lanzhou, even with a terrifying average score of 72 µg/m3 still only made 36th place in the global league table of shame. The word’s worst polluters as of 2014, drum roll please, are to be found in South Asia, with Pakistan taking four of the top twenty slots and India taking thirteen, including the top four. And number one? Delhi. Well, at least India’s finally first in something…

The question now, however, is how the hell did it get this bad? Research shows that environmental awareness is close to a maximal saturation point, more people are mobilized, more green initiatives are being proposed in governments all across the globe, and just a few weeks ago, a record breaking climate change demonstration took place in New York in advance of the 2014 United Nations Climate Summit. The Summit is the first time in five years that world leaders are again attempting to rally international support for a global agreement to reduce greenhouse gases emissions.

And whether you believe the majority of climate change scientists or not, at the very least you have to admit to the adverse health affects that a buildup of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere have. As all NYUSH kids know, you shouldn’t be able to taste air, let alone physically feel it giving you lung cancer with each breath. Greenhouse gas emissions are either going to lead to a global natural disaster, global health crisis, or both. And all sane people would agree that these hazards are well worth preventing, thus the need for global action. In addition, targeting greenhouse gas emissions would not only reduce air pollution but also water pollution, land pollution and resource depletion. But that’s an article for another time. The point is, that although the majority of world leaders see the threat and the non sustainability of current levels of global GHG levels, and meet every few years at the UN to work towards a global treaty agreement for lowering each nation’s emissions, each attempt so far has largely been a complete and utter failure and, in fact, as long as our focus remains on universal national cooperation, it will continue to be so. Let me explain. The first treaty to bring countries from around the globe together was the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. First negotiated in 1992, the UNFCC had 156 signatory parties, who upon ratification vowed to reduce atmospheric concentrations of GHG within their borders. This treaty worked under the idea of “common but differentiated responsibilities model” which argued that developed countries should take the lead on addressing GHGs but all parties would make general commitments. Developed countries agreed to return their emissions to 1990 levels. From this treaty came the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which extended the UNFCC into the 2000s and operated under a similar differentiated model. Countries like China and India argued that history must be taken into account when we consider the situation we currently find ourselves in. They argue that our current climate is the product of 200 years of rapid industrialization and unchecked pollution by the United States and Western Europe. These rich nations therefore have a moral responsibility to correct for their historical legacy and allow more leniencies to developing nations to grow their economies and lift their people out of poverty. And with the creation of the UNFCC it seemed as if most developed countries would peacefully go along with this differentiated model.

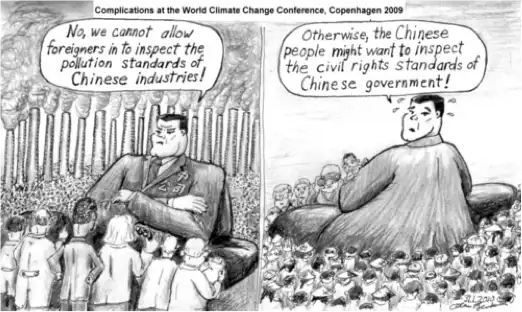

However, in 1997 the United States refused to sign the Kyoto Protocol because it saw the agreement as unfair: balking at the idea of having to take on the heaviest burdens of the agreement while the emissions of China and India ballooned rapidly out of control as well as taking an economic hit in terms of slower or even stagnant growth. This move prompted Canada to become the first country to withdraw support from the Kyoto Accord because according to the Canadian government, the treaty was useless if it did not bind the world’s main sources of pollution to it. Russia supported the decision and Japan refused to extend its obligations to the Protocol past 2012. Which brings us to our third attempt at a global climate treaty: the Copenhagen Accord. They say the third time’s the charm right? Well not quite. The Copenhagen Accord should have laid out a strategy to handle the global emissions problem past the Kyoto’s Accord’s expiration in 2012. Instead, what we got was a watered down version of Kyoto that did…nothing. It set no goals, no binding limits, no punishments, nothing. In short, it was not worth the ink it was printed with. So why do all these agreements keep failing? Is it the nature of the conflict itself? Or is the United Nations a completely useless institution? I’m not a complete cynic. I think the United Nations and its various branches have done tremendous good for the world. Whether it’s in public health, children’s rights, women’s education or human trafficking, the UN is a shining beacon of all that is good about humanity, like love, commitment and compassion. But in the domain of controlling GHG emissions, all the UN has accomplished are shallow agreements, which have absolutely no significant global impact, done all in the name of “cooperation”. And no wonder. In international diplomacy, it’s often difficult just to get two nations to agree on common ground, let alone one hundred and ninety three! All sides involved are quick to point fingers, of course and they all have good points. In one sense, developed countries like the United States are to blame. It’s not just their historical legacy. They currently have the highest per capita emissions. They also control most of the world’s wealth, their citizens have the highest standards of living and on average over consume the earth’s resources. While India, despite being the largest polluter, suffers from widespread poverty and lack of infrastructure. It’s new prime minister, Narendra Modi, ran on a campaign pledge of providing toilets to every home. Toilets. In addition, the economies of many developed countries are shifted away from manufacturing based to technology or service based. Instead it is developing nations that are becoming industrial strongholds and as China well knows, manufacturing emits a lot of GHGs. But in another sense, developing nations like China, India, Brazil (part of the top five largest polluters) are also at fault. In the Kyoto Protocol for example, the sole responsibility to make GLOBAL emissions reductions large enough to meet the goals of the treaty were left in the hands of just thirty-eight governments, including Japan and the U.S,

while 137 other nations including China and India were in compliance with the treaty even if they did not reduce emissions or if they even increased emissions. And while some of the compliant thirty-eight countries dramatically reduced their emissions and transformed the ways they consumed energy, it was not nearly enough to even begin to slow the monstrously increasing levels of CO2 coming from developing nations. Not to mention the blatant disregard some industries within nations like China show for international environmental standards. Moreover, fines for polluting or for violating environmental standards are so low that factory owners often prefer to pay rather than implement cleaner technologies. We can not continue down this path. There’s too much at stake. The problem with the United Nations and the UNFCC in particular, is that it is too inclusive. We’re always taught that inclusivity is a good thing but in the case of actually getting meaningful, binding treaties passed, too much of a good thing is…like a cancer. In general the more inclusive an organization is, the harder it is for that organization to demand significant changes in behavior and compliance from its members because of the parallel significant difficulty of setting rules and institutions for the monitoring and enforcement of the rules. Instead, what might work better could be smaller treaties worked out between a few nations. Institutions with smaller memberships work better because they have less diversity and less diversity means that there is only a limited range of preferences for policy choices. As the number of members increases, the more diversity you add, the wider the range of policy preferences becomes, and the greater the chance that a certain small group of members will block the cooperative efforts of the whole group in order to move policy towards their own preferred option. And as we’ve seen with the UNFCC, with Kyoto, with Copenhagen, what ends up happening is that in order to get everyone to agree to “cooperate”, negotiations end in shallow, non binding treaties. I want to emphasize that starting with smaller groups does not eliminate the option for an eventual global collaboration later on. Take the Montreal Protocol for example. Widely heralded as the most successful environmental treaty ever, The Montreal Protocol is a treaty implemented in 1989, designed to phase out the production of numerous substances, such as CFCs, that are responsible for ozone depletion. It was followed by only a small group of signatories at first but later grew to include almost all countries. Trade provisions in the treaty limited signatories to trade only with other signatories. Those in close trade relationships with each other were forced to mutually sign the treaty in order to maintain their valuable economic ties. In addition the Multilateral Fund was established: it provides incremental funding for developing countries to help them meet their compliance targets and builds capacity within these governments. Global climate change treaties going forward could benefit more from using models like this. For instance, the United States and Brazil could sign a bilateral treaty in which each country sets emissions limits at a certain amount-the US could provide some kind of funding assistance to Brazil in exchange for certain trade rights, or something similar. Then the treaty could potentially expand to include other South and North American countries. But something that I think is even better than bilateral or small multilateral agreements between nations are agreements between actors that are even smaller. These smaller treaties can even be between two cities or a group of cities. The C40 for example, is a collection of forty major cities from all around the world who have independently come together under the launch of a global Compact of Mayors. The aim of the C40 is to establish collaboration among local governments of different global cities to make deep GHG emissions reductions. Mayors have the power to address as much as 50% of urban emissions. The C40 website outlines an plan of specific actions that signatory mayors can implement in their cities to meet target requirements. They target everything from urban planning and infrastructure, to waste, to public services, to water, to technology but are all wide reaching and accessible options. It’s actually something I’m personally very excited about. The idea that we need to wait for global national treaty before we can affect real change on GHG emissions is a pernicious and unhelpful myth which we need to work to dispel right away. All around the world right now, smaller actors are taking an active role in our environment and in the health of our communities and linking with other small, likeminded actors all around the globe. The C40 is one example but there are countless others also beginning to emerge. In an article in the New York Times, Rajendra Shende, former head of the UN stratospheric ozone protection program, writes about many such groups. “The Rockefeller Foundation announced that it would disinvest all its assets in fossil energy starting with $100 billion. Over 180 institutions, organizations and pension funds have begun to follow. The Global Agricultural Alliance was launched to enable 500 million farmers worldwide to practice climate-smart agriculture by 2030. Climate and Clean Air Coalition, a voluntary group of nearly 100 states and non-state actors pledged to reduce short-lived greenhouse gases such as black carbon, methane and hydro fluorocarbons.” Today, despite the failure of the UN to achieve a global treaty, we have more hope than ever. Communities, businesses and small coalitions are forming all across the world without any international agreements and are the ones spearheading innovation and change. We don’t need the UN to act as a treaty creation organization, we need them to be a medium through which coordination is fostered, as an early warning system, and to identify the gaps between actions undertaken and actions still needed. Let’s face it. The time has come to give up on a global climate change treaty. We’re so much better off without it. This article was written by Rae Dehal. Send an email to opinion@oncenturyavenue.com to get in touch. Photo Credit: Dave Burnham @ Flickr