Does the Global North Owe a Climate Debt to the Global South?

The Global North’s wealth was built on the exploitation of the Global South’s resources and people—it's time to face the growing calls to repay this "climate debt."

Photo by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung

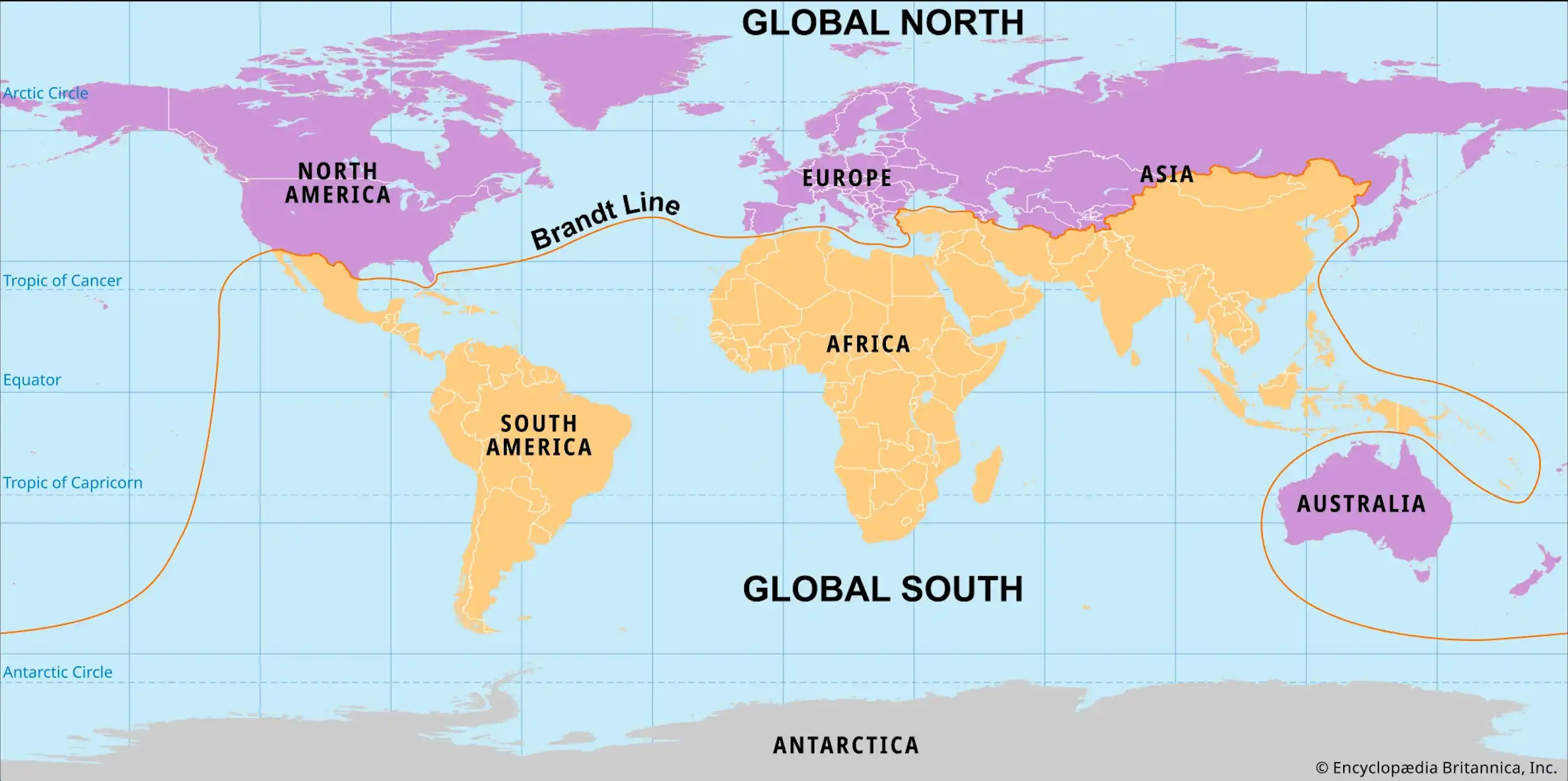

“Climate debt” can mean many different things, but it generally refers to the idea that wealthier countries have disproportionately caused climate change while the effects are disproportionately felt by poorer countries. As a result, wealthier countries should assume a larger responsibility for mitigation and adaptation costs that countries of the Global South collect. The Global North (which includes most of North America and Western Europe) owes a debt to the poorer countries of the Global South. Countries are not yet on equal standing, as those countries who colonized have unjustly burdened the nations they once occupied. This injustice extends beyond the extraction of resources, the violence of colonial governments, or the oppression of local rights; The Global North has irreversibly damaged the physical environment of the Global South and of the world.

Map of Global North and Global South

It is worth noting that these boundaries are fluid and can change depending on the source.

Photo by Britannica

The governments of the Global North now uphold a double standard, demanding that developing countries uphold environmental protection measures that the North did not themselves follow on their path to “modernity”. The only right to this double standard is to hold the North accountable for the destruction that they caused in the Global South. From this accountability is born the concept of “Climate Debt”. By understanding “climate debt” as a form of “structural violence” scholars have suggested that the same social mechanisms/ideologies that sustained the development of the Global North prevented and continue to prevent the same development from occurring in the Global South.

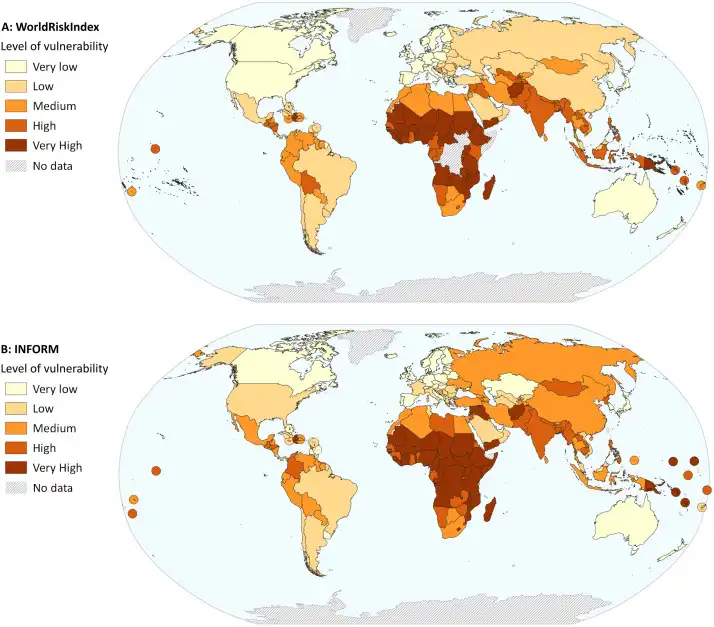

Global vulnerability maps based on (A) WorldRiskIndex and (B) INFORM index

Birkmann, Joern, Ali Jamshed, Joanna M. McMillan, Daniel Feldmeyer, Edmond Totin, William Solecki, Zelina Zaiton Ibrahim, et al. 2022. “Understanding Human Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Global Perspective on Index Validation for Adaptation Planning.” Science of The Total Environment 803 (January):150065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150065.

Photo by ScienceDirect

The primary social mechanisms I am referring to that perpetuated this unequal development are extractivism and colonialization. Extracivism is a worldview that understands natural resources like trees, rivers, mountains, and even the ocean as a commodity with the sole purpose of being utilized by humans. Colonialization, the more well-known of these injustices, is more than just the control of a foreign territory. In turn, the government ultimately defines locals as sub-humans who are undeserving of the right to self-govern. These ideas together allow both the land and people as a source to be exploited. These two worldviews were key to the historical colonial project that positioned the Global North to view themselves as above those of the Global South and justified extracting natural resources for their sole benefit.

This moral obligation that the Global North has to provide compensation to the Global South has been popularized by the Environmental Justice Movement. This social movement seeks to challenge the inequalities that traditional environmentalism is organized around. By centering the idea of fair treatment and meaningful involvement, the movements advocate for “no population to bear the disproportionate share of negative environmental consequences”, even if the consequences were suffered in the past, or will be suffered in the future. As much research has shown, poorer countries are going to experience the worst of the consequences of climate, consequences largely the fault of wealthier countries. Simply put, it’s not just. Developing countries don’t have the money to pay for the infrastructure necessary to save themselves from the problems they have been burdened with.

Secondly, climate change is a threat multiplier. It amplifies pre-existing issues, such as “natural” disasters and food insecurity, making them increasingly harmful. Countries in the Global South are not only prevented from developing on the front of not being able to create emissions to stimulate growth but also from the perspective of addressing the damages caused by the environmental impacts of already emitted greenhouse gases; acting as both a source and a sink for climate change impacts. They are dealing with environmental issues at face value and the sociopolitical and economic impacts such as resource competition, political destabilization, and climate migration.

These issues are compounded in the sense that the sociopolitical and economic impacts of climate change further prevent these countries from being able to build their capacity to adapt. An example of this could be that countries of the Global North such as the United States and the European Union in recent years have made large-scale investments in subsidizing clean energy to “reduce climate debt”, yet this is not an option for countries in the Global South, as they lack the financial resources. In other words, poorer countries have no other option but to maintain a system destabilizing their environment. This further enforces the obligation that countries of the Global North have to provide reparations to the Global South.

The concept of debt is troubled in this context. In mainstream discourse, while the damages climate change causes are primarily physical, debt repayment is insinuated to be fiscal. However, giving money to the Global South will not simply undo or prevent the effects of climate change on their societies. The North has been delinquent on this debt for decades, and it has since accrued untold interest due to the severity of climate change. There is an “obligation to repay [the] historical overuse of the carbon commons by freeing up an equivalent amount of sink capacity for the future use of the debtors”. This adaptive debt is a system based on compensation that “means to transfer finance or technology that enables the same degree of ‘‘development’’... without the emissions normally attached”.

I understand this to indicate that not only does the Global North have a moral obligation to repay a “climate debt” to the Global South, but that a larger emphasis has to be placed on resource mobilization that encompasses forms other than monetary compensation like technology transfer). Moreover, the right to sustainable development predicates how countries in the Global North operationalize “paying their debt” to the Global South. The idea of a “climate debt” asks us to question the same social mechanisms that created the circumstances it is ultimately trying to mitigate– which has made the discussion more difficult and critical to creating more equitable outcomes in a world increasingly impacted by climate change.