3 Life Lessons I Learned from Competing in a $450K Gaming Tournament

“A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies, said Jojen. The [person] who never reads lives only one.”

- G.R.R Martin Thirty minutes from now, you know you’ll either be celebrating proudly or staring listlessly like you dropped a freshly baked cake on the floor. The most existential part about these games, whether physical sports or cerebral engagements, is that they start, you act, and it’s over. You do what you can with the completely real possibility of mistakes. You write the fate of the game in ink. And sometimes, there is no “next time” to do better. That’s it. In chess you at least have time to think before each move - the characterized pieces of the game are in stasis while the players of the game are in turn-based thought. I’m going to move my knight only after I’ve simulated the other possible moves I can make. To a point, most of chess occurs in the mind of the players, relishing in the suspense of decisions. On the other hand, in most athletic sports it’s not wise to sit and think. You’ve got to keep moving. I’m not going put my body on hold in water polo to think about to think of what to do next. Firstly, the ball’s still in play, and the time I spend thinking still is time that could be spent on moving. Secondly, I would probably drown. But interestingly enough, in procedural sports, often you enter the “muscle-memory” high - where your body is gliding effortlessly in second nature and your legs move themselves.

You dive into the water, and start treading.

So chess and water polo have their methodological challenges, but they both have their avenues of leeway. If you could mix the worst of both worlds… A CHIMERA OF STRESS When you combine the pressure from both settings, in the case of an online real-time multiplayer computer game, you get conditions where there is no pause button, and your thoughts are constantly engaging in a non-physical abstraction. Your physical body is out of the picture and unable to share the load, and your chess-oriented mind takes on the whole burden. That is, you better hope that your mind is ready to flow, because the most your all-empowered muscled body can do is smash your laptop out of anger (you’d probably disconnect and lose the game). Really, in these games it’s correct to presume: physically you’re just sitting in a chair, and although your fingers may be jackhammering away and maybe your mouth is enunciating the ‘f’ consonant at an unusual frequency, it’s something that a scientist from an evolutionary perspective would say is extremely not natural. From the outside, it’s a crazed phenomenon to absorb in the happenings of a computer screen. On the inside, it’s even crazier. To understand, games involve their players warping into a world that’s hard to share outwardly if one is not also immersed in the action. Just like witnessing someone in daydream where you spot their glazed-over face, or the scratch of the chin when you see someone rapt in the world of a book (yes, a piece of paper with scribbles), their mind is entered into another world. It’s like seeing 100 people sitting still (mostly) in a dark room with a projection on one of the walls. It’s like me seeing someone moving weirdly, all the while not knowing that they’re just dancing, listening to music I’m too far from to hear. When you’re playing a videogame, you are teleporting yourself to some place just as salient and engaging. It’s the same venture of worlds we enter in books, stories, poetry, comics, movies, music, and introspective contemplation. THE TREASURES OF NEVERLAND Even one that has never felt these immersive experiences may still find something valuable in the lessons gathered from a group of NYU Shanghai students who chose to practice daily and stay up until 10am in the morning to press some buttons on their computers, competing against 700 other university teams across the US to help pay for their college tuition. The competition is to promote a new game by Blizzard (World of Warcraft, Guild Wars) called Heroes of the Storm. This is similar to the popular League of Legends, DOTA2 games that many people play and are even paid to participate in with “e-sports” nowadays. The game has 5 people facing another 5, blazing through a map to take down the other side’s base. Imagine capture-the-flag in the forest, but once you reach the flag, you need to successfully destroy it. An important thing to consider here is that you’re playing alongside other real players, which means the social context is complicated. Your mind is playing realtime chess against 5 other people. You’re a mathlete. So as we will see, what you learn from competing in a team game tournament is that the simplest situations and simulations, when given two or more people, can turn into a chaotic branching of infinite possibilities, risk-analysis, brain-twisting empathy, bottled aggression, and most saliently, a proxied reality.

FIRST LESSON: FIND A GREAT TEAM There was a guy named Napoleon Hill in the 1900s who hung out with Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie, also researching those like Edison and Lovelace. He spent his life finding what all those highballers had in common that made them so damn successful. In Carnegie’s Buzzfeedily titled classic, “Think and Grow Rich”, he establishes that they were keen on the idea of a “mastermind team”. It is people who together have skills which compliment each other. A mastermind team fills the holes and cover the bases, together being more robust than any one of them alone in standing. It’s the marketer, programmer, and thinker. The extroverts to the introverts, the good cop and the bad cop. It’s the Bonnies to the Clydes, the effectual oligarchy, the dream team. Those who did not work well with others, no matter how talented, may be prodigious in passing but in the grand scheme would not be effective. They had to have a mastermind team:

I was the tank. The Tank, in these MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena) games, does what it sounds like: he/she rushes into battle and takes all the fire from the enemy so that the teammates behind can stay protected. Taking the brunt of the attack, a tank may remind you of a martyr or masochist, but rest assured that damage would not be taken if not for the good it allowed. The rest of the team ought to do their part.

The DPS is the damage-per-second role. Teams get pretty optimized and down-to-the-dollar when you’ve got things on the line. These are the people that, yes, can dish out the most attack power every second. These are the economical ones: mileage per gallon, GDP per capita, bang for your buck…damage per second. Because of this efficient power, the tradeoff given is that they are often weak if you can target them directly. As you can see already, the Tank is the hulking sacrifice meat-shield, while the DPS does its job if they can get a shot in edgewise. Though these two by themselves are still not enough to have a robust team.

The Support heals teammates. So when the Tank is taking all the heat and the DPS is waltzing in attack, the Support is there as a medic, to provide life when people’s lives are running low. Without them, you won’t have much immunity. Like with a high-rise, without sturdy support, you’re likely going to fall. So this little triumvirate can be abstracted to all sorts of contexts. You need the bravado of a tank sometimes—and other times, the acuity of a DPS, or the compassion of a support. A mastermind team can essentially be a good balance of these three traits. You’ve got to know who each person is, what they’re good at, how they operate, and how to protect them. The first step, long before the timer starts, is knowing who you are as a team, and being self-aware enough to gain insight from that. A cooperative, listening team with a tight-fitting bond will do wonders over those who are in a tunnel-vision, individual state of mind. SECOND LESSON: HAVE EMPATHY AND QUOTE DONALD RUMSFELD There is a whole other group though, in their own dorm at Ohio State or MIT or Montana State, competing against you. Those players on the other team - you don’t know what they’ll do. You can’t see where they are. You don’t know what their plan is. Much like real life, you’re going to need emotional intelligence to predict what these others are going to do. In this game though, the empathetic fog-of-war is like not being able to see 20 feet in front of you on an especially polluted day, when your life depends on it. You need to try to your best ability to forecast the moves of people you have never met in your life. If you’re out alone in the game’s jungle area and you fail to predict your enemies approaching to destroy you, you’re going to have a bad time. Like in real life, you only can gleam from what’s in your reach and what people tell you. All else is up to inference, probability, insight, and simulation of “what would I do if I were them?”. Indeed, Adam Smith’s sympathy comes through experience. An empath is a fair person to have on your team, to predict what other people would do in situations, and act accordingly based on that. No one’s empathy is perfect, but it just has to be effective enough. The thing is, empathy is pretty hard to do through a computer screen. NYU’s Adam Brandenburger gave a talk last semester about economics and game theory. In his office at Stern in Washington Square, he took time out of his day to expand on how neuroscience is expanding the frontier of Nash’s renowned more-than-Smith conjecture— what’s now called epistemic game theory is the field of considering how people’s thoughts are about other people’s thoughts. That is, as long as we have the power to think of what another person is thinking, it’s unpredictability all the way down. This is what often makes economics a psychological practice more than a mathematical one. We’re rational human beings, but also sometimes stubborn ones. Sentient markets are wild cards. So in this game, you are thinking what the opponent is thinking, but don’t forget that they are probably thinking of what you’re thinking…of what you’re thinking of what they’re thinking, to infinity. You’ve gotta have economic intuition with the information you’re given.

Simulations are patterned.

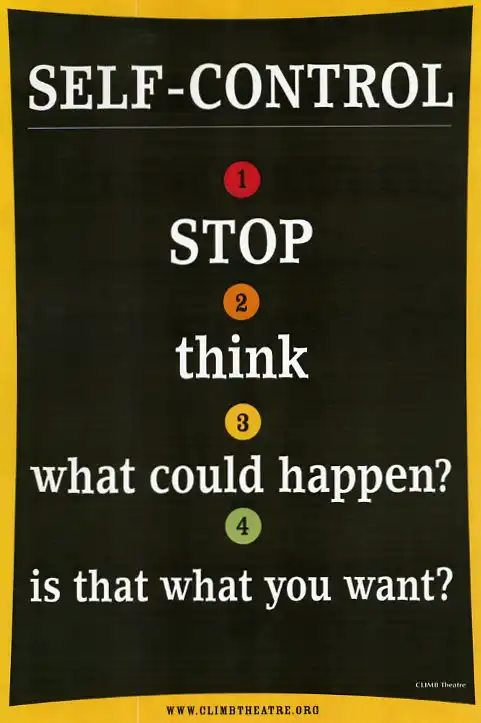

So exactly what information are you given? You have three lanes to choose from in the game — all leading to Rome, or your base. It is economical to distribute between the lanes and assign one or two people to travel down each one, mathematically. But since it’s so economical, isn’t that what most people would do? And if you do the same thing, isn’t it just going to butt heads? People are more than rudimentary math and machines, if they choose to be. In one of our games, we decided to all stay together as a united five, and not split up, contrary to what is usually suggested. That means two of our lanes were vulnerable — but that also means when we ran into the probabilistic one or two enemies in one of the lanes, it would be us 5 against their 2. Then we could move to the other lanes and do the same. It would not be a fatigued war of attrition as many battles so often are. Just one of extreme risk. And honestly when we employed this, we knew it was a risk. So sometimes going against the grain will get you into trouble, but other times it will give you an edge up. It’s situational and requires context. We took this approach with a team from Montana State, but how about Caltech? Not so much. They probably have crazier strategies than we do…maybe. THIRD LESSON: IMBUE MORALE AND SOLID MOTIVATION There’s a simple acronym that all the players exchange before the start of every game: glhf. “Good luck, have fun” is the contractual nod that embodies loving your “enemy”. It says, “No matter what happens, we’re both playing this game by these arbitrary rules because we are more alike than we are different. And although we’re at odds in this case, it’s a part of the experience we’ve both agreed to”. Tournament settings give you an immersive sandbox, where both sides agree to give it their all, while at the same time respecting each other. So with this competitive context, if your overall goal is to win, you had best act like it. You do a little huddle with your team beforehand. And when the gates release, you’re cheering each other on, building each other up. Again, the game’s being calculated all in your head—you can’t activate fight-or-flight, or any of that bodily Herculean brutality, because then you’ll stumble on a key or two. You’ve got to keep your eyes and fingers keen. The confidence needed is a blue, Stoic one. You can flex your muscles or appear bigger, but what good will it do? The equivalent of good posture here is a clear mind.

So let’s say an enemy has just killed your teammate. You may at first impulse rush after that enemy in an angry flurry for revenge. This is a conflicting situation, but the game again is a sandbox that teaches you what Gandhi or Martin Luther King Junior may suggest—because often times, doing things by impulse is what creates trouble in the first place. If a team seeks an eye for an eye, it may lose all its vision and you may dig yourself further into an unpleasant situation. What a team can most effectively do is envision a holistic goal: in the bigger picture, this involves not closing off to the world of short-term battles. Sometimes you have to take a humble step back and check out what you really want. This means sometimes being open to failure. What psychologists would call this today is a growth mindset—this is the start-up creed of failing faster, because you learn more from failure than you do from success. It’s acknowledging that things are not diamond, not static, which means if you are not good at something right now, you can get better at it if you work at it with passion. Likewise, it’s knowing that most people have reached their awesome levels of skill not by innate betterness, but by making a promise to master it, and putting in the raw work and time into improving and anguishing through. People are not born knowing how to master a three-lane game and click at insanely high speeds, but they put their noses to the grindstone. Teams who are immune to failure but who are optimistically ambitious are likely to grow in ability much, much faster than the players who don’t download the game because it seems hard. If you want to win but are afraid of losing, that tournament stays a “what-if” instead of lessons learned and possibly passed down to others. So in the heat of the game behind the keyboard, you’re cooperatively yelling at your teammates, commandeering to go right, go left, top, bottom, Alfa, Bravo, Foxtrot, every which way. You still high five when you get a pentakill, and it’s okay to go through the emotions. That’s your morale, the excitement. You don’t have to become a wantless monk to point things in a dedicated direction. But a key thing to notice is that you never lose sight of what your end ambition truly is, to not get too caught up in any one thing. It's easy to forget that. AFTERWORDS OF AN APOLOGIST Now, a high school student made a promise to cut down on video games a long time ago, and agreed to do this tournament because free tuition ain’t so bad. Starting as early as six years old, a kid can play strategy games out the wazoo, starting with a little chess set, games on the scale of civilizations such as Civilization, history such as Age of Empires, physics such as Portal, creation such as Minecraft, and atrocious economies such as Eve. You’ve got lots of worlds in your head. I don’t believe that games inherently are good. They indeed can be a horrible waste of time. But in the growth mindset mentioned before, you can choose to learn lessons from anything if you are so open to them. It is in these other worlds where lessons come the most quickly and most abundantly. They say a person lives one life, but a person who reads books can live thousands of lives. Immersive portals such as movies, stories, and history teach us by proxy. They say don’t learn from your mistakes, but from others’ mistakes when you can. By this right, these activities are simulation engines packing many different doses of experience per gram. It’s a monster meal of wisdoms and perspectives. If someone reads a diverse range of stories, watches movies with dynamic characters, immerses in the global history of the world, engages in open-ended environments, and openly searches for the lessons passed down from others, they have effectively fostered insight that cumulatively took many lifetimes over in the making, even if they themselves have only existed for so long. Likewise, a person controls one life, but a gamer can control thousands of lives. Just think if you had 2 bodies that could roam different parts of the world at the same time. How much more accelerated would your experience of life be? Now imagine that with the infinitely, expansively roaming worlds created in games, and I guess that makes it pretty cool. Just make sure to take time to live and learn things in this world too. CAVEATS: CAN I TREAT LIFE AS A GAME? Do not think that this means you can treat life as a MOBA, or god forbid an FPS (first-person shooter). There are boundaries between immersive sandboxing and what practices can be extracted to outside. A distinction: in real life, most people (I would hope) do not want to engage in any sort of combative struggle. You are on the same team. We enter a civilization because we look out for each other and we work to think about how everyone can live in unison without hurting or eating each other. In a game, you may want to win and will do what it takes to decimate the enemy, but again, that’s because both sides agree to play. In this case, you didn’t agree to be born. It sounds funny but it’s true. It’s a bit more real here, and there’s real things at stake. Only select principles can transfer over from the free-for-all of gaming. Team dynamics still apply. When fighting big issues such as poverty, pollution, or other large things stacked up against us, you’ve got to have an efficiently cooperative government, a tight organization, a level-headed movement. (If your government has more infighting than addressing of issues, there might be a bureaucratic bottleneck. If your movement creates more stigmatic hostility than reasonable explanation, then you’re not going to get very far in trying to say your word.) Empathy still applies. If we could all share the same mind and thoughts, that would make for a wildly boring world. Though what we have here is, for better or worse, a reality where you are the captain of your thoughts and your thoughts only. We only have language, communication, and empathy for all outside knowledge of other people’s thoughts. You could only know how much people tell you or what you can extract from the nuanced subtleties of human behavior. And of course, some people in their sentient nature may also act a bit against the grate, the wild cards. In a world full of feelings, empaths will always have a place. Morale still applies. The goal is to keep going. Some people are struggling to survive, or some people suffering just as much internally. Sometimes you need motivation to make it through tough moments. Morale in light of a bigger goal will empower you. And if it doesn’t hurt others, and if you think you can take it, try all sorts of new things that you think you might enjoy. Make a promise to become better, push through. No lie, every failure will still sting and hurt and gnaw a little bit of you, but these are the hot coals on the way, the burn of exercise, leap of faith, and the focus of discipline that comes with every improvement. No large thing comes without it. [embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEcQrILxTlc[/embed]

Yahoo CEO Mayers in an interview speaks about trying new things.

Most of all, life is not about winning, but about playing. If you’re a staunch evolutionary strategist, then maybe you’d want to be the fittest. But at 7 billion, it’s okay. You have your family, sure; your school spirit, okay; your culture/country, go for it; your clique, fine. Though, it’s important to realize that it’s seldom an ends to bring others down.

There are no strict enemies. Most people just want to be happy, and if you want to talk about economics, the thing is to try to do it so that people can be happy without other people being sad. It’s to implement thoughtful codes of conduct (society in essence) and promote the greater good. Game theory is indeed at the heart of this. It’s not only laws, but the way we treat other “players”. Conflicts are a bit more personal in the real world, so it ought to go: I don’t know the other person’s story and what they’ve been going through, so I can understand their actions and give them the benefit of the doubt. I’m not going to ride on assumptions or prejudice and will try my best to communicate through any misunderstanding. It’s more than a matter of GDP and points, because there is emotion involved. But at the same time, it is more than charity and involves good thinking.

Both contexts of games and real life can be pretty enjoyable, but it’s the losses we have to be mindful of. In a game, people that receive damage can often respawn or can just quit the game if it’s irritating enough. But in life, you’re an agent of potential permanent influence, and you might only have one chance to play, no pause. That’s the distinction between treating a game as a game and treating a life as a life. Do not conflate the two. GOOD LUCK, HAVE FUN Life is serious enough. Teammates went off for Spring Break and called those all-nighters a fruitful experience. Finals for the tournament are streaming on ESPN. On that sleepless weekend in March with 1 loss and 2 victories, we won against formidable university students (who weren’t so sleep-deprived). If we could do that, what else could we do? It's the the gem of having lived in other worlds– in books, games, legends, dreams. You get out there and try. "It ain't about how hard you hit, it's about how hard you can get hit and keep moving forward, how much you can take and keep moving forward. That's how winning is done!" - Rocky Balboa Sources 1. J. Von Neumann, O. Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton University Press. 1953. 2. N. Hill, Think and Grow Rich: The Complete Classic Text. New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2008. This article was written by Michael Lukiman. Send an email to managing@oncenturyavenue.com to get in touch. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons