Street Maps and Incorrect Coordinates: Issues Involving Online Mapping in China

It is raining outside, pouring. A Shanghai woman has agreed to meet her friends for dinner in Puxi (浦西) and her shoes are already soaking. The idea of the venturing all the way to the metro station -- struggling against the animal-sized rain that often plagues Shanghai -- is daunting to say the least. So, the woman decides to call an Uber. A few minutes later she receives a phone call from an eager Uber driver inquiring about her exact location. In China, the driver’s GPS system restricts him to knowing only the user’s general vicinity. Meanwhile, everywhere else in the world -- Australia, United States, Great Britain, etc.-- the additional Uber phone call verifying the location of the user is superfluous; the exact coordinates of the user are already given. Every other country in which Uber operates is not subjected to the specific rules and regulations established by the People’s Republic of China. Foreign entities are not permitted to use accurate geographical information in China. According to articles 7, 26, 40, and 42 of the Surveying and Mapping Law of the People's Republic of China, private surveying and mapping activities have been illegal in mainland China since 2002. The law prohibits entities that have not obtained special authorization from the Department for Surveying and Mapping under the state council from freely using correct GPS coordinates. What does this regulation mean besides the additional annoying phone call from an Uber driver? For NYU Shanghai’s Anna Greenspan, it meant a complete game change for the curriculum of one of her courses, Street Food and Urban Farming. Last April, Greenspan noticed that the project her students had been working on -- one that involved collaborative mapping through an online mapping program called CartoDB -- was experiencing technical difficulties. “The map we had constructed displaying the locations of street-vendors at night literally just turned black,” Greenspan explained. Initially, she assumed that the difficulties were simply a result of human-error; surely the vast discrepancies in location could not have been caused by the system itself. It was not until the mapping team at NYU Shanghai -- consisting of Anna Greenspan, Clay Shirky and other notable professors -- took a closer look at the problem did they realize that the issue was much larger than originally thought.

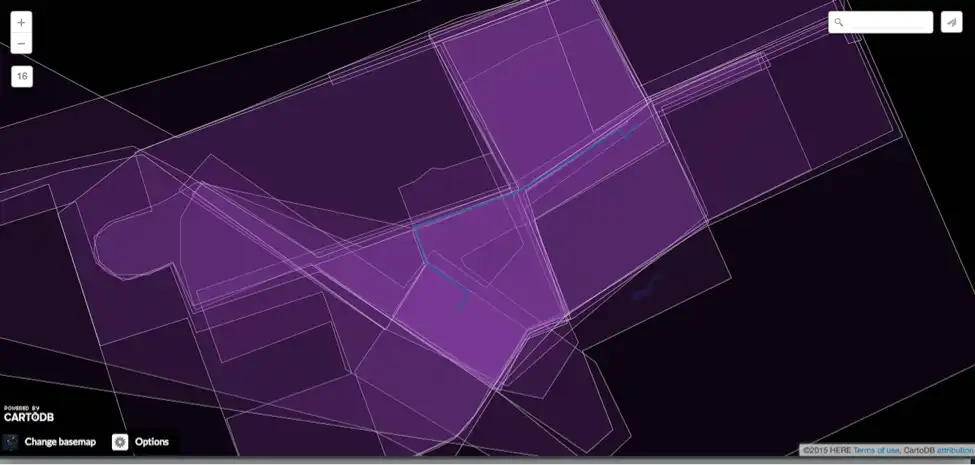

(Image of Greenspan’s Empty Night Map)The cause for headache is as simple to explain as it is difficult to navigate around: an automatic offset established by the People’s Republic of China. Specifically, the issue is referred to as the China GPS Offset problem, and is associated with a class of issues stemming from the difference between the GCJ-02 and WGS-84 datums, or coordinate systems. In layman's terms, the two different systems prevent maps from lining up; coordinate points will literally appear at the incorrect location. Brief investigations reveal that the cartography in various locations in China have been shifted (about 0.025°E,0.025°S in Chengdu/0.06°E in Beijing) according to services such as Google Maps. Meanwhile, a quick survey of Baidu and Sosa Maps (two Chinese companies) report everything lining up perfectly.Besides technical difficulties as a result of Chinese legislation, Greenspan and her students also experience roadblocks involving the presence of foreign mapping services (or lack thereof) in the Middle Kingdom. Originally, Greenspan’s students utilized Nokia HERE maps as a basemap for their research. In April of 2015, around the same time Greenspan’s students were to publish their maps, Nokia announced that its mapping service, HERE, would no longer operate in China, Hong Kong, or Macau. Dr. Sebastian Kurme, the Communications Manager at Nokia, announced that the “regulatory environment means that we [Nokia] have not been able to apply the same business model in China that we have had success with elsewhere.” As a result, Nokia made the decision to shift its primary focus to other markets outside of China.China’s regulations on geographic information is a hard-to-see problem with effects that are difficult to unsee. As the Middle Kingdom looks ahead to expand its economic influence across the hemispheres and around the world, how will its administration handle future deals involving online mapping? This may be the end of HERE maps in China, but it is surely the beginning of a larger problem for the People’s Republic of China. This article was written by Lillian Korinek . Send an email to managing@oncenturyavenue.com to get in touch. Photo Credit: Anna Greenspan