GPS Debunked: A Breakdown

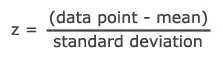

Recently, there has been a lot of confusion for the freshman population surrounding GPS. As we all persevere through the grueling yet familiar process of midterms, more and more questions regarding the grading system, and simply the functioning, of GPS have surfaced. OCA spoke with Jeffrey Lehman, NYU Shanghai’s Vice-Chancellor, in an attempt to clarify some of this confusion. GPS Structure The courses that we associate with GPS are the GPS Lecture, GPS Writing Workshop, and GPS Recitation. GPS as a whole is two entirely separate courses stitched together: the lecture with recitation attached, and then the entirely separate Writing Workshop. Writing Workshop is then divided into two separate courses: Writing Workshop 1 (basic writing) and Writing Workshop 2 (advanced writing). Students are placed into these classes depending on their English proficiency level. Over the summer, all freshman were sent a survey inquiring about their language background. If a student checked the box that said that English is their first language, he or she was automatically registered into the Writing Workshop 2 Course. If a student checked the box that said English was not his or her first language, only after taking an English placement exam would the student be placed into the appropriate writing workshop course. Writing Workshop 1 and Writing Workshop 2 are in themselves different courses. The basis of grading for Writing Workshop 1 is completely separate from Writing Workshop 2, and the grading system and objective for both writing workshops are completely separate from that of the GPS recitation/lecture. The only consistent factor between the recitation/lecture and the Writing Workshops is the texts that students analyze. GPS Grading System The grading system for the lecture/recitation is designed in an attempt to neutralize whatever advantage native English speakers would have. The breakdown of the grading system is as follows: Midterm One: 20% Midterm Two: 20% Final: 40% Participation: 20% Midterm and final grades are tricky to calculate as there are seven Global Post-doc Fellows, each of whom teaches two recitation sections. Students are graded on their three essays on a scale from 1-6. Within each professor’s classes, grades are fitted to a curve to make grading more uniform across different sections. However, this curve exists within each recitation leader’s combined classes, meaning that when students take their midterm, all three hundred grades are not fitted to this curve. Professor Lehman explained that, “It would be arbitrary and unfair if one GPS professor had a more generous interpretation and that was reflected into students’ grades.” So, each recitation leader grades his or her students own essays. Then, they send their grades over to Professor Jeffrey Lehman, who follows a statistical process called normalization to evaluate the grades: The student’s test score is the “data point”, the “mean” is the average of all the recitation teacher’s students scores, and the “standard deviation” is the quantity that expresses how much student’s scores differ from the mean value. What is calculated is called a “z-score” which might be familiar to anyone who has taken Statistics 101. This allows us to compare relative points on one even plane.

After normalizing students’ grades, Professor Lehman sends the scores back to the recitation leaders, and engages in a dialogue to verify that the grades reflect how the recitation leader perceives his or her students to have performed. Recitation leaders can single out students and alter specific grades in relation to Lehman’s line. Prof. Lehman explained that this last step makes the “process more personal.” During OCA’s conversation with Vice-Chancellor Lehman, he insisted that, “everyone is graded the same: there’s no way for the recitation instructors to know who is writing... they can tell if someone is clearly not a native English speaker, but not the students’ specific ethnicity.” There has been much speculation in regards to the standards by which students are graded, as some students argue that because a professor can identify a native English speaker, the standards by which students are graded will vary depending on how well they articulate their ideas. Furthermore, one could argue that it is unreasonable to assume that a person who cannot understand the text as thoroughly can articulate an interpretation as clearly as someone who is well versed in English texts and has been communicating in English for their entire lives. However, despite this questionable equality, Prof. Lehman insists that, “if you present a muddy analysis in a perfectly grammatical way, the fact that its perfectly grammatical won’t help you. If you present a brilliant analysis in a non-grammatical way, the grammatical errors don’t hurt you. The writing part is in Workshop 1 and Workshop 2.” GPS In theory Professor Lehman was most enthusiastic about the goal of the class. “What makes it stand out is that it is a required course for all 300 students in the first year, which makes it more visible and manifest. .. But it’s awesome, and it’s been an unbelievable success. . . when I look at how much more sophisticated everyone is about cultural difference and similarity than they were when they arrived, it is amazing. It’s phenomenal. Students from all cultures, not just separating Chinese and others, but among others and Chinese, help students understand differences across culture. People are just more attuned to what might seem like a disagreement on the surface is really just a reflection of cultural difference.” The goal of GPS this year, according to Lehman, is to set up more cross-discussion, and ForClass is the medium through which to do so. While students all wait in terror at the thought of being selected and forced to answer questions into a malfunctioning microphone for two hundred and ninety-nine other students all secretly rooting for them, the process by which students are chosen is not random. “The selection isn’t random at all,” Vice Chancellor Lehman explains, “it would be a waste of everyone’s time to call on the people with careless answers.” Selections are based on ForClass. “With ForClass, the questions are embedded in the text when students are answering, and I can see this before everyone gets to class. And I can see, ok there's a vote, which ended up being 60/40, which suggests a division. I don’t try to map the division by ethnicity, but I pick students from each side, and I often will try to pick students who are going against the stereotype. I might do it on a gender basis, where someone might have a gender stereotype.” Reflecting on how using ForClass has affected the quality of the class, Prof. Lehman commented that, “Last year, I was just calling on students randomly. I think it is substantially better this year. It really varied a lot from class session to class session. For example, if it were midterm week, people wouldn’t be prepared. This year, even during a stressful week, people seem to be prepared.” What to Expect Because GPS is so specific to NYU Shanghai, the course is constantly being reevaluated. In terms of grading and structure, Prof. Lehman plans to keep the system the same. However, next semester, there will be three guest speakers, each of whom will teach two classes. The topics will be on gender, science and religion, and relativism. One of the speakers, Prof. David Hollinger, will be a returning speaker from last year. Vice-Chancellor Lehman described the speakers as, “some of the most distinguished scholars in the world today. They are stunningly fabulous people.” As students have just finished their second midterm and, like myself, will be eagerly awaiting a score, it is important to remember the premise behind the class before dismissing a grade as unfair. It may seem that NYUSH is attempting to do something nearly impossible: pushing together approximately 300 students from different cultures and expecting them to analyze complicated texts in an equally insightful way. However, one must admit that it does create an interesting atmosphere to learn in. Lehman explains his faith in the practicality and success of the class in the future, “It’s a big course. It is a personally satisfying course for me because we’re talking about issues that when I was a college student, I didn’t imagine would be coming back over and over again in my professional life, in different phases. These things come up unbelievably often. When you first read them, they can seem very abstract, but then you start to encounter situations that test them, and they become very useful.” This article was written by Zoe Jordan. Send an email to managing@oncenturyavenue.com to get in touch.